Sure, you can borrow my shuriken!

You got to hand it to Cannon Films. Along with Carolco and New World Pictures, they led the pack in low-budget B-movie production during the 1980s. Sadly, these studios are defunct now. Like so many stalwarts of the Eighties, these were devil-may-care, hair-in-the-air, nose-on-the-mirror exploitation grindhouses. They burned bright (Carolco did launch The Terminator and Rambo franchises), and burned quickly. But Cannon, however, had its own marketable niche – the ninja.

Ninjas were to the Eighties what superheroes are to the Aughts.* Boyhood, action-packed fantasies come to life on the big screen – some minimal outstanding work, and a lot over-bloated crap. Yet what the ninja film never fails to demonstrate is its durability – even a bad ninja movie is still pretty good. But Cannon didn’t care either way. They made a habit of snatching scripts out of the dustbin and watching the results with tongues firmly in cheek. It may seem all harebrained to the sophisticated minds of the cinema elite, but if you were a kid growing up in the 80s, the death-defying, acrobatic, martial arts sorcery of the ninja made total sense – at least until you realized covering yourself in black doesn’t make you invisible to anyone.

How the wave of the ninja entered the global film market began with a book. Eric Van Lustbader‘s The Ninja introduced the world to martial arts’ lonely master, Nicholas Linnear, in 1980. A success, the book stirred an appetite for the nearly superhuman ninja assassin. One year later, enter the ninja… literally that is the name of the movie.

Although not directly based on Lustbader’s novel, Enter the Ninja does pit the “western ninja” against the old, rival nemesis – a consistent them throughout ninja culture. Like The Ninja, Enter the Ninja gained a popular following and became the first in what is now regarded as Cannon’s “Ninja Trilogy.” The films are not directly related by storyline, but all contain the martial arts majesty of Sho Kosugi.

A former All-Japan Karate Champion, Kosugi is a criminally overlooked action star that filled a much-needed gap between Bruce Lee and Jet Li. Along with the Ninja Trilogy, Kosugi starred in a plethora of low-to-mid-budget martial arts movies during the 80s, including Pray for Death and Black Eagle, an early Jean-Claude Van Damme co-starring vehicle.

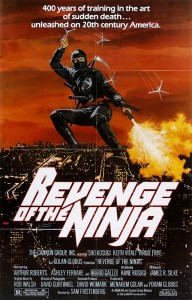

Now for those who’ve never seen or heard of the Ninja Trilogy, here’s the inside tip: the second film is the runaway star of this series. Revenge of the Ninja (1983) single-handily set the bar for the modern myth of the big-screen ninja, and is virtually unmatched in its balance of over-the-top action and realism.

Revenge of the Ninja either established or developed many of the stealthy-near-supernatural skills that separated the anti-heroism of the dark ninja from the nobility of the devoted samurai. Poisoned shurikens, chained whips, flame throwers, smoke bombs, and even life-size ninja decoys are all part of the arsenal used to unprecedented effect throughout the film. And 20-foot leaps through the air are easily broken through superior ninja ankle strength.

Okay, it’s a little stupid. But it’s a ninja movie, and as far as ninja movies that don’t force you to suspend your disbelief too far go, you could do a lot worse than ROTN. The acting is respectable, the plot is solid, and at 90 minutes, its lean on self-indulgence. Yet what truly makes this film so laudable is the climatic battle atop an L.A. high-rise between our good ninja and our bad ninja. Before their grand duel, the two adversaries share meditative gestures that seem to reflect honor and code, which becomes ironic moments later when they leverage every opportunistic advantage to kill each other. Again, it doesn’t have to make sense.

The final film in the trilogy, Ninja III: The Domination, took the series in a much more mystical direction, which may explain its modest reception compared to the first two films. Other ninja movies were released as part of the Cannon catalog throughout the 80s and early 90s, including the American Ninja series and a bevy of Chuck Norris flicks (these sorta count). Few, if any, however, received positive critical responses. The popularity of the ninja movie began to wane shortly after 1990. A number of guesses exist as to why, but it’s reasonable to speculate the sub-genre suffered a similar fate to the video game crash of the early 80s. The market became over-saturated. Often when a niche market has too many so-bad-they’re-good items it reaches a plateau when each fan has his or her one so-bad-its-good item and a myriad of options is not needed. Ninja films may be consistently entertaining, but without enough ROTNs to keep audiences reeled in, well, sometimes bad pizza really is bad pizza.

*I’m including Aughts as 2000 – 2012. It’s just easier this way.